The crisis that would eventually cost Dr E five months of her career did not begin with a missed diagnosis or a clinical disaster. It began with a deadline every working parent in Britain understands with familiar dread: the nursery pickup.

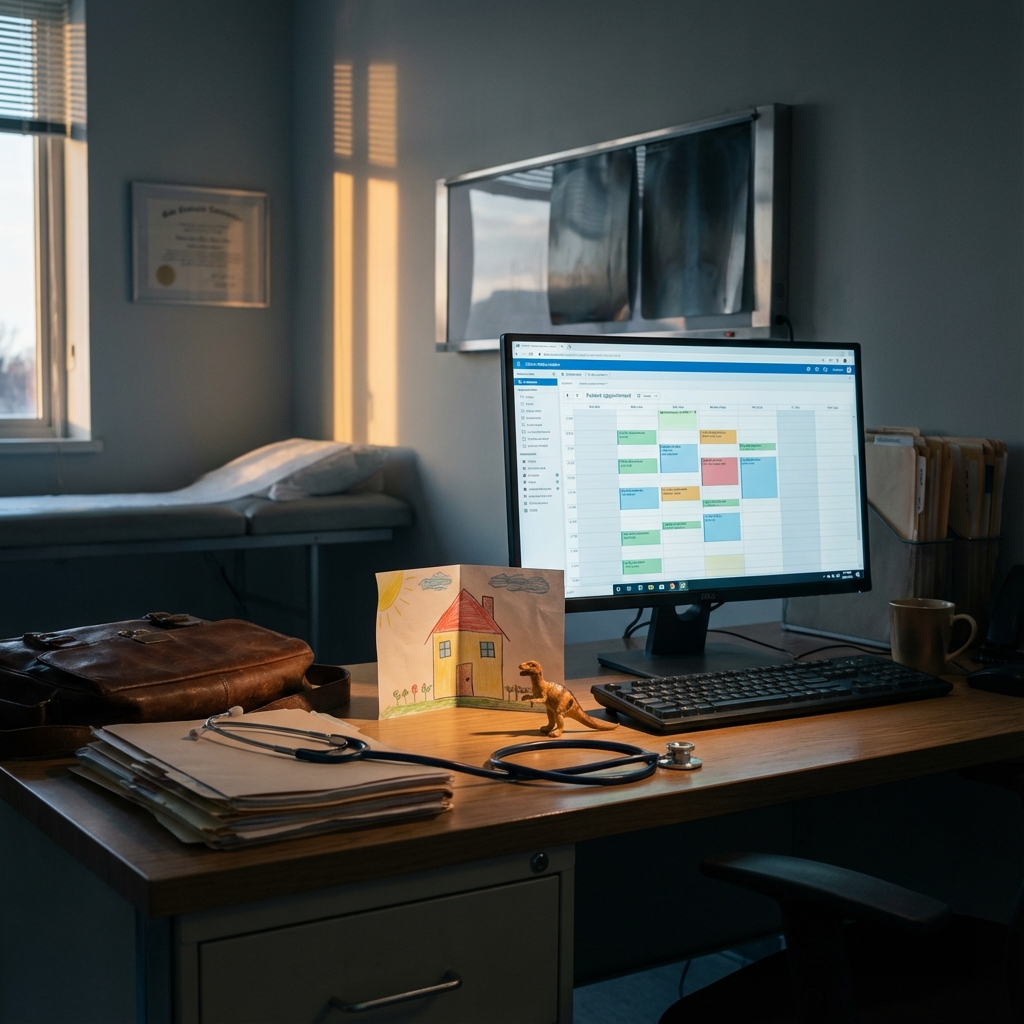

The time was 4.30pm on Wednesday 17th July 2024. Dr E, a salaried GP at a busy medical centre, was staring at her appointment screen and the clock. She was in the grip of a specific panic. She had three young children, her husband was working away and she had not slept properly in weeks due to “long night-time waking hours”. She also had a hard stop. She had to leave by 6pm or lose her childcare provision.

In the unforgiving reality of general practice, 4.30pm is the danger zone. It is the moment a complex emergency can walk through the door and derail the evening. Caught between professional duty and parental necessity, Dr E made a decision born of exhaustion. She blocked out two face-to-face slots with the names of patients she had already spoken to on the phone. They were “ghost” bookings, placeholders designed to buy her twenty minutes of safety so she could leave on time.

Two days later, on a busy Friday, a partner at the practice queried the anomaly. Panic led to cover-up. Dr E logged into the record of “Patient B” and typed a lie. She documented a physical examination that never happened to justify a consultation that never took place.

Last month the Medical Practitioners Tribunal Service (MPTS) handed down its verdict. For this error of judgement and the year of denial that followed, Dr E has been suspended for five months.

On paper, the verdict is legally sound. Falsifying medical records is a red line; it endangers patients and destroys trust. But look closely at the transcript of the hearing and you find something more significant than a dishonest doctor. You find a clash between two different worlds—the rigid, black letter law of medical regulation and the messy, exhausted reality of the NHS workforce.

To understand why this case has become such a talking point for the profession, we must look at the argument raging between regulatory purists and safety advocates.

The Orthodox View

The position of the regulator—let’s call it the Orthodox View—is clean, circular and legally robust. It posits that honesty is the bedrock of medicine. If a doctor can fake a record to make a school run, the logic goes, what else might they fake?

The tribunal’s determination follows this logic precisely. It identifies two fatal flaws in Dr E’s conduct. First, the act was premeditated; she logged back in two days later to cover her tracks. Second, and perhaps more damningly, she displayed a “sustained lack of candour”. When confronted in August 2024, she lied to her colleagues. She self-referred to the GMC in September but was, in her own later admission, “not as open” as she should have been. The full truth did not arrive until October 2025, over a year after the event.

In the eyes of the regulator, insight is treated as a proxy for future risk. Because Dr E hid the truth for a year, she is viewed as a “medium risk” to the public. The suspension is therefore not a punishment but a necessary quarantine to “signal norms” and maintain public confidence. You may disagree with the outcome but the logic is consistent. Serious dishonesty plus late insight equals suspension.

The Systems View

But there is a competing perspective, one that we at the Doctors’ Association UK have long championed. Let’s call this the Systems View, though it is also the bedrock of our campaign ‘Learn Not Blame’.

From this vantage point, Dr E’s dishonesty was not a fundamental character flaw. It was a “human factor” failure. She was not a rogue element seeking financial gain; she was a drowning swimmer grabbing at a raft. The tribunal accepted her context—sleep deprivation and the absence of a “fallback” plan for childcare—but treated it merely as mitigation for a crime rather than an explanation of a system failure.

The regulator is operating on an obsolete model of safety. In the aviation industry, a pilot who makes an error under extreme fatigue is not immediately dragged before a court. The airline investigates the roster that put a tired pilot in the cockpit.

By contrast, the GMC’s model is adversarial. It is a courtroom, not a cockpit. This adversarial posture actively incentivises the “lack of candour” it claims to abhor. When Dr E was first questioned, she lied. Why? Because in a culture of blame, admitting “I blocked a slot because I’m overwhelmed” feels a bit like a professional death sentence. The system scares doctors into silence then punishes them for not speaking up.

I would argue that the logic “they cannot repeat it while suspended” is formally true but regulatorily lazy. It substitutes absence for intervention and creates a moral hazard: punishment masquerading as protection.

A true compassionate regulator would not simply remove the doctor. It would manage the risk through supervision, local change, potentially some conditions and mentorship. These are interventions that actually ensure the behaviour isn’t repeated, rather than simply hoping a five month exile will fix it.

The Systems View reveals the wider damage of the Orthodox approach. By suspending Dr E, the MPTS has removed a competent doctor (described by colleagues as “exemplary”) from a practice already short of staff. It has fined a young family five months of income in a cost of living crisis. It has done so to protect the public from a risk—a tired mother blocking an appointment—that is far better managed by support than by suspension.

Norm Enforcement vs Risk Management

The fault line in this case is the difference between ‘Norm Enforcement’ and ‘Risk Management’.

The tribunal, representing the establishment, sees its job as enforcing norms. Dishonesty is unacceptable so it must be sanctioned visibly. Public confidence, in this view, requires a visible sacrifice.

We see the job of regulation as managing risk. Risk is situational, not dispositional. Dr E is not a “dishonest person”; she is a person who acted dishonestly in a specific, high-pressure situation. Removing her does not fix the situation. In fact, it arguably harms public confidence more by leaving patients without a doctor than by allowing a remediating clinician to work under conditions.

The reality is that the current system is not designed to optimise workforce retention, family stability or system learning. It is designed to demonstrate boundary enforcement.

This is exactly why aviation and rail safety moved away from adversarial blame decades ago. The problem is that medical regulation has not.

What Happens Next

Dr E will return to practice in five months. She has been ordered to attend a review hearing where she must demonstrate her “insight” into stress management. She has not yet indicated an intention to appeal and, given the admitted facts, a legal challenge would be an uphill battle.

Whilst the legal case may be closed, the policy wound is wide open. There is a deep irony here. She is being told to learn how to manage stress by a regulator that has just subjected her to the most stressful event of her professional life. The predictable challenge of balancing the NHS with motherhood has been met with a clumsy punishment.

This case is a clear example of why a punitive, adversarial model produces outcomes that are misaligned with patient safety and workforce sustainability.

Until the system changes, we are left with a regulatory architecture that functions as judge and executioner. It effectively tells the NHS’s exhausted workforce: if you are drowning, do not grab at a rope that breaks the rules. It is safer to go under than to reach for a lifeline and face the tribunal.

Note: I have chosen not to name the doctor in this case. The MPTS determination is publicly available for those who wish to read it, but my interest here is in what the case reveals about regulatory culture, not in adding to one clinician’s digital footprint.

Dr Matt Kneale is a Clinical Fellow in Emergency Medicine and Co-Chair of the Doctors’ Association UK (DAUK).